Jail Break!

One of the frustrating things when studying the efforts of anti-apartheid campaigners in the 1950s and 1960s is seeing how the might of the South African state was so successful in closing off avenues of protest and in criminalising dissent. Prominent South African activists, even when not detained, found themselves voiceless due to banning orders.[1] They were also frequently harassed by the police and often were threatened with arrest. My research has paid particularly close attention to the Rivonia trial of 1963-64, but this trial was just one prominent example of many such prosecutions, and a particularly significant success for the South African Government in its attempts to remove the influence of the anti-apartheid movement in the country. Anti-apartheid protest within South Africa was hit to such a degree by the mid-1960s that it took years to recover. In the years following, it was reliant on a network of anti-apartheid campaigners working around the world to continue the fight. When reading about this unstoppable march to repression, despite the best efforts of those fighting it, any small triumph means a lot.

In my last post I wrote of the arrests that took place at

the Liliesleaf Farmhouse; arrests that led to a trial that would have a

far-reaching impact on apartheid. The

owner of this property was Arthur Goldreich – a South African artist and

communist. He was not at home when the

security police raided in the afternoon of the 11th July 1963, but

he was detained when he arrived back in the evening. Had things gone to plan, he likely would have

stood trial along with the other Rivonia trial defendants and would likely have

received a life sentence along with the others.

Also detained shortly following the Liliesleaf Farmhouse

raid was South African lawyer – and again communist – Harold Wolpe. He was arrested near the South African border

with Bechuanaland (present day Botswana) while in disguise and trying to leave

the country. He too would have likely

been among those tried in the Rivonia trial.

His wife, AnnMarie, was the sister of James Kantor who was among the

line up of defendants in this trial. In

my last post, I mentioned that Kantor’s arrest and prosecution was widely

presumed to be a response to the failure to place Wolpe on trial.[2]

The reason why Goldreich and Wolpe didn’t feature in the

Rivonia trial was due to their jailbreak and clandestine flight out of South

Africa, across the African

continent, and finally to the UK.

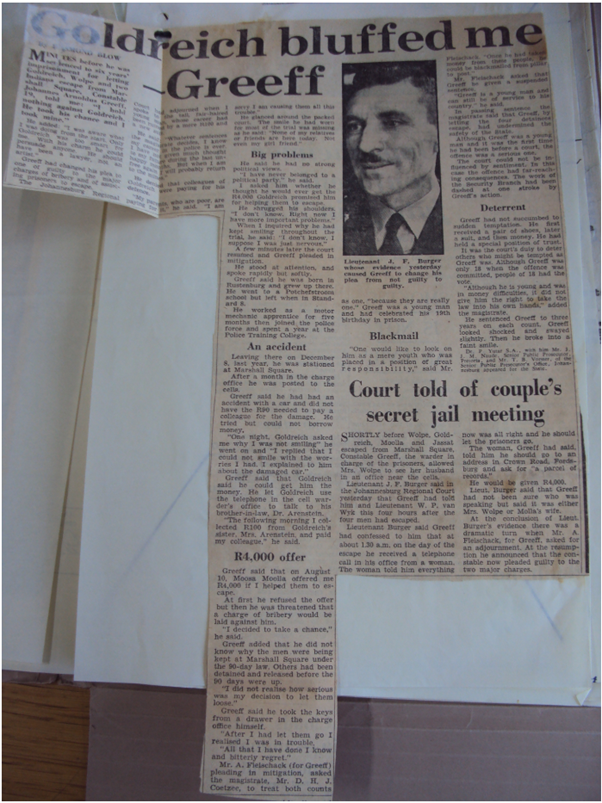

Goldreich and Wolpe were held together at the Marshall Square prison in

Johannesburg. Their escape

revolved around persuading a young Afrikaner guard, Johannes Greeff, to give them the keys to their

cells. Greeff was in financial

difficulty, having crashed his friend’s car and owing R100 (£50) for the

repairs. In exchange for being allowed

to use the prison telephone, Goldreich told Greeff to call his sister and she

would give him the R100 he needed.

Following this, he was promised R4000 (£2000) for his help, and on the

agreed night, 11th August, Greeff unlocked four doors.

In addition to Goldreich and Wolpe, two members of the Indian Congress, Moosa Moola and Abdullai Jassat

were also planning to escape.

Once the prisoners left the building into the night, carefully

laid plans went awry, as is all to common when reading such stories. The car that was due to meet the men was not

there; the driver having waited outside the jail for 45 minutes before assuming

that something had gone wrong. Seeing

that there was no car waiting, the four men took the decision to split up, with

the Wolpe and Goldreich going one way and Moola and Jassat going another.

In a more fortunate turn of luck, after walking for a long time, a car

stopped to offer Goldreich and Wolpe a lift and the driver of the car happened

to be a friend. They were taken to a

house in the Mountainview suburb of Johannesburg, where they hid for a week

with the curtains drawn and making no noise that would alert neighbours to

their presence.[3]

Meanwhile, back in the jail, the plan was for Greeff to injure himself sufficiently

to make it look like he was taken by surprise and knocked out. Greeff was unable to hurt himself

convincingly and his involvement in the escape of the prisoners soon came to

light. He went on to face the full anger

of the government, and presumably many of his friends and family. He was tried and sentenced to the maximum six

years in prison. Because of this Greeff didn’t

received the money that he was promised.[4]

The second attempt was more successful with another plane

arriving at a more remote airstrip.[9] This plane took them to Elisabethville

(present day Lubumbashi) in the Congo (present day DRC).[10] Danger continued to follow them though, and I

have found an account of a possible attempt on Goldreich’s life in an

Elisabethville hotel:

From the Congo, the men arrived in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanganyika

(present day Tanzania). Both Moola and

Jassat managed to evade the police and made their way to Tanganyika too,

although I haven’t been able to find the story of how they managed to make

their way out of South Africa and north to safety.

Both Goldreich and Wolpe eventually travelled to safety in the UK and settled here. Goldreich continued his work as an artist. Wolpe taught sociology at the University of

Essex until going back to South Africa in 1991.[13]

As a final thought to round off this post, the risks and

sacrifices of South Africans who were involved in fighting against apartheid

cannot be underestimated. So many men

and women gave up everything to fight for racial justice. While the stories I am retelling of well-known

trials and jail breaks are interesting and significant, those who formed the

ranks of campaigners who were arrested, harassed, beaten, tortured and killed are owed

a huge debt. Goldreich and Wolpe upended

their lives, and the lives of their families, for the cause. But both men had the means and the opportunity

to leave the country and remake their lives as part of a growing diaspora in the

UK, to be greeted as heroes by those supporting the anti-apartheid

movement. This was not possible for the

vast majority of South Africans who were not White, whose names are not noted

in the history books, but whose collective contribution was crucial to the

fight for racial equality.

[1]

Banning orders were restrictions that meant that those subject to such orders

were unable to attend gatherings above a certain size, were unable to speak

publicly or have their words published, and they were unable to travel far due

to a requirement to check in with a police station on a regular basis.

[2]

Kantor was acquitted midway through the trial due to the weak evidence provided

by the prosecution. The charges against

him were very spurious and, for this reason, his defence was conducted by a

separate team to those of the other defendants.

He was determined to prove his innocence in a way that the other

defendants had no hope in doing. Though

he was acquitted, the strain that his detention put him through and the harsh

treatment he experienced ruined his health and he died ten years later on the 2nd

February 1974 of a massive heart attack when he was just 46 years old. Before his death he wrote an autobiography –

An Unhealthy Grave.

[3]

Much of this story can be found at the start of Joel Joffe’s account of the

Rivonia trial: Joel Joffe, The State vs. Nelson Mandela: The Trial that

Changed South Africa, (Oxford, Oneworld Publications, 2007), p1-9

[4]

There were moves to honour this debt in the 1990s though, so hopefully this was

finally settled! The

smiling policeman: Not every Afrikaner in the apartheid security apparatus was

a monster. More than 30 years ago, policeman Johan Greeff did 'the Movement' a

favour. Now he may receive his reward | The Independent

[5] “Rand

Daily Mail, 25 September 1963”, enclosure Dunrossil to Foster 27 Sep 1963,

10112.89, JSA 1641/28, FO 371/167541, The National Archives of the UK.

[6]

This was not an easy feat. Wolpe had earlier been arrested trying to leave

South Africa while disguised.

[7]

Bechuanaland was one of the High Commission Territories along with Basutoland

(present day Lesotho) and Swaziland. As

Bechuanaland had yet to achieve independence from the UK, there was some sense

of obligation placed upon the UK to be involved.

[8] Clark

to the Secretary of State, 7th September 1963; embtel 308; POL 30 Defectors

& Expellees SAFR; Box 4032, Pol 25 Demonstrations, Protests, Riots S Afr –

Pol Sarawak; Central Foreign Policy File 1963 (Box 4032); Record Group 59

General Records of the Department of State (RG59); National Archives at College

Park.

[9] I

have been unable to find out who exactly arranged for this plane to be sent. It came from somewhere in east Africa, but

that is all I have managed to discover. I need to dig round more archives!

[10]

Apologies if using the name the Congo is an anachronism. I believe this is the

correct name for the country in 1963, but I am not 100% familiar with all that

was happening in this part of Africa at this time.

[11] McNamara

to Secretary of State, p2, 10th September 1963, tel 226; POL 30 Defectors

& Expellees SAFR; Box 4032; Central Foreign Policy File 1963; RG 59;

National Archives at College Park.

[12] Leonhart

to Secretary of State, 17th September 1963, tel 308; POL 30 Defectors

& Expellees SAFR; Box 4032, Central Foreign Policy File 1963; RG 59;

National Archives at College Park.

[13]

Sadly I arrived at Essex over 10 years too late to have run into him!

Comments

Post a Comment